When the Road Calls Your NameGenerously contributed

|

|

I crossed a continent, an ocean and an island and now that I stood

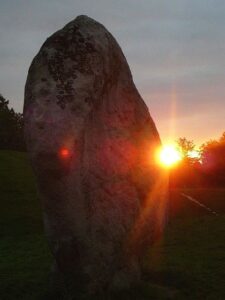

Looming over the English curator, the elderly American demanded through loose lips, “What’s so special about this place, huh?” “Well,” smiled the curator, “Avebury is the largest stone circle in the world…” “Saw it. Is this the whole town?” “The modern town of Avebury sits entirely within the ring of …” “What’s the museum for?” The American angrily shook England’s October chill from his Hawaiian shirt. His voice dripped with contempt that the country’s temperature did not fit his tourist’s uniform. The curator replied patiently, “We house a small collection of artifacts discovered…” Out thrust the American’s finger. “What’s this?” “I’m glad you noticed that display. This…” “It’s a rock. We have rocks at home. We don’t build museums for ‘em. Do you have anything good?” Before the curator could indicate his prize display, the tourist declared, “I’ve seen it.” The Ugly American turned his back and shoved past me out the door, his wife remora-like at his side. The curator turned his eyes on me, propped up his smile and nodded in greeting. I admired his resilience — something I had long lost. “Is there anything I can help you with?” he asked, glancing over my army surplus ski-jacket, weathered jeans and I took off my glasses and polished the mist from them. Not trusting contact lenses on a rough trip, I wore an old-fashioned pair of sturdy black frames. I had stopped shaving the day I quit my job and it suddenly occurred to me that I had not seen another bearded man since I had arrived on the island — as if I needed an appearance guaranteed to distance me further from those around me. But I was not thinking of appearances when I withdrew my savings, tossed a few things in an old army backpack and flew away over the great Californian desert, across the wide states and over the rough Atlantic, reversing the course of my westward-driven forebears. Embarrassed at seeing myself through the curator’s eyes, I was about to demur, but considering the brush-off the man had just received, I changed my mind, saying, “Actually, yes. I’m particularly interested in the excavation of The curator’s smile became genuine and he swiftly ushered me to a series of photographs of neatly stacked finger bones and skulls within the Long Barrow. The more questions I asked, the happier my white haired acquaintance became. Consequently, it took me three hours to complete my examination of the small room’s treasures. We had long since introduced ourselves. Eventually the curator apologized for keeping me so long. I assured him that it was I who had taken his time and that I was delighted and grateful for the information. I pulled out a small wad of bills to poke into the museum’s donation box. The curator caught the tiny hesitation as I swiftly calculated how much I could afford to put in. He asked, “You’ve I had scarcely talked to anyone in weeks and was in no mood for confidences, but my countryman had been coarse and this man kind. I affirmed, “I have many more to see before I return.” “You’re not exactly an archaeologist, are you?” asked the curator, subtly eyeing my travel-worn clothing. “But My journal pressed uncomfortably against my chest. I adjusted it, and the man glimpsed the small, black-covered volume. Perhaps he thought it was a Bible, as he asked, “Are you a spiritual person?” “I prefer not to define myself,” I said uncomfortably. “Yes, but are you? Are you on some sort of pilgrimage?” Awkwardly, I pieced together what answer I could, though it is not easy to explain to a stranger that you feel derailed, that your locomotive is on the grade spinning iron wheels in gravel, that a lifelong dedication and a quarter century of work seemed like maybe they had some weight in your hand and then vanished without a trace. But I let him know I felt a need to stand where my ancestors left their bones. The curator absorbed this with a crisp, unmoved, English smile. “You were in the Sanctuary, earlier, weren’t you?” I was a little surprised. “Yes, I meditated there awhile.” “People will do that occasionally. Not much goes on here without we know about it pretty quickly.” He eyed me. I replied carefully, “I want to spend several days here. There’s a lot to see.” “It was pretty early when you were in the Sanctuary.” “Yes, I have a limited amount of time — and money — and a long way to go.” There seemed no point in not admitting the financial pressure he had clearly deduced. “Are you staying under a bush somewhere?” he asked lightly. “Pardon me?” Though amused, his smile was friendly. “You don’t have a car and you were at the Sanctuary before the first bus “I’m…I’m trying to find…” He interrupted smoothly, “You know, the nights here do get rough.” “I’ve managed so far.” “There’s a bit of weather coming in, and if you are sleeping under a hedge somewhere, it could be unpleasant. He took a deeper breath, knit his brows a trifle and peered into my eyes, asking, “You aren’t bothered by dead “I…can’t say I ever have been,” I replied, “but I’m not really sure what you’re asking.”

“I’m not sure I do.” “There are people interred inside, you know. That wouldn’t bother you?” “Not at all. It’s just that a church is…well…” “It’s there to help people. Not just people of the same faith. It’s warm and dry and never locked. No one will be there on a weekday evening. The rector comes in at six in the morning. If he should find you there, just tell him I Seeing that I did not know what to say, he added, “It’s there if you need it.” Then he shook my hand and went out to tend to other business, as did I.

Walking along what remains of the megalith-lined causeway connecting the vast stone ring to the Long Barrow, I sought some echo of the spiritual bond that had, so long ago, inspired men and women armed only with antler picks and reindeer shoulder blades for spades to heap up an artificial hill called Silbury, raising it from the flat ground like the monumental green breast of their beloved earth mother. There it stood, a thousand generations

I thought of Ezekiel preaching to the dry bones and bidding them live again. Perhaps in a place of ancient wholeness I, too, might find renewal. My emptiness being curable by no rational means, perhaps the irrational could help me. I burned the rest of the day’s dim light photographing the ancient complex, as best I could in the worsening weather. By nightfall the storm was harsh. Well wetted from my day’s excursions, I could not face sleeping again tucked under a hedge in a water-resistant sleeping bag wrapped in a tarp.

Stone is not a good mattress, and a wild British storm is no calming lullaby, but long walks and a yawning cavern in the soul make it possible to still the mind until consciousness sinks beneath the waves, and eventually I floated into otherrealities. I woke with a jolt. Someone was there with me. Or sort of a someone. I sensed an awareness without form or substance. I could no more describe this feeling to one who has never had it than I could describe sound to one born deaf, but whatever sense it was that had seized my attention, I felt that presence as clearly as I felt the stone beneath my body. There was nothing to see, no sound really, though I was vaguely aware that thestorm still swept and pattered at the church walls. I had been trained to believe that such things did not occur. Yet there the presence was, as focused on me as I was on it. It wanted me out of there. Its antipathy was inexplicable, tremendous — and growing in intensity. It wanted me out. Out into the night. Out into the storm. Out and as far away as possible. I had little idea what to do. There was no question of convincing myself that it was not there, or of getting back to sleep. A roaring man would have been easier to ignore, and less upsetting. Perhaps, whether or not I could make sense of it, I could treat the presence like a person. Talking seemed unnatural in that dead quiet, yet I might, in a sense, press my own feelings back against that alien presence pushing at me. I concentrated, projected my reasoning: “Yes, you make me feel awful. Yes, you fill me with dread. But I’m not The hostility swirled about me, worse than before, incredibly unpleasant. “I mean no disrespect,” I insisted, “but I need shelter. And I was offered it. Look, I don’t know if I can ever afford to come back to this country, but I do know I can’t afford to get sick. I’m not going out in the storm.” The more reasonable I became, the more the disembodied outrage swelled. I felt besieged by a spiritual storm as buffeting as the weather outside. “Stop…pressuring me. Stop with the vibes, already. I won’t go out tonight, storm or no. I don’t like being pushed, psychically or otherwise. Leave me alone. Let me sleep. It’s been a long, hard trip, damn it, and stone The pressure became almost physical. I found myself leaning against it. This was too much. A friend and teacher had given me an ancient symbol of wholeness, cast in polished pewter. She had taught me its history and symbolism and how to meditate upon it in times of trouble to still the mind while holding unwanted influences at bay — usually meaning one’s own bad memories, destructive thoughts, or pressure from actual living people. I had never expected to use this meditative discipline to protect myself from the hostile awareness The symbol was not there. I had put my glasses in the same pocket and the symbol had been there then — it must be near at hand. I patted my palm about the floor and bedding, blindly searching, finding nothing but stone and cloth. I could accept the existence of a ghostly presence sooner than this disappearance of a familiar object. I refused to admit to any trepidation, but fear began to seep into the fringes of my consciousness. My hand found the edge of the rolled jacket that served as my pillow, slid underneath to feel about. Nothing. Where could it be? I had to have it — it was my only defense. The more I concentrated on finding the symbol, the less I concentrated on pushing back the hostile presence and the more my fear began to rise. I picked up the coat and shook it, expecting to hear the pewter expelled from some fold to clink against the stone floor. Nothing. Instead, the pressure of the unseen entity swelled to such unimaginable power that I actually felt as if great hands reached underneath the edge of the sleeping bag and started to lift me up and push me back. My heart pounded, adrenalin shot through my system, my limbs flung themselves out to the sides, trying to hold on to the stone floor. I awoke, disconcerted. I had felt so awake already. No dream in my life had ever felt so conscious as this — none had allowed me to think so clearly — and none had ever so completely reflected my waking experience. Because there I was in the pitch-black church, now wide awake, and there was the same presence I had felt in my dream, still wanting me out, out and away, gone for good. The same pressure was there, but no longer overwhelming, no longer physical. While I had been unknowingly asleep, the force had grown stronger the less I focused on holding it at bay. Now that I exercised the full power of my conscious mind, the pressure exerted by I groped for my pack, found the pocket and pulled the symbol from its resting place. I ran my thumb across the smooth metal, feeling its shape, picturing the symbol in my mind. Doing so held the hostile presence at bay. There was no escape from its relentless pressure, and it prevented me from sleeping, but it could do no more. I lay for hours in the utter dark, cramped on the hard stone, picturing the symbol and pushing the entity to the edge of my awareness. At last, I felt the change when night invisibly but palpably shifts toward day. With the change in the air, the presence faded and at last I could drift into exhausted sleep.

I caught the bus and traveled onward, filling my empty eyes with new sights of old things. But in my dreams each night, I dreaded the return of the hostile entity, and when, sometimes, it did return, I felt terrible waves of raw fear — a horror of…I knew not what. Dread wore on me. I had to understand this experience and to bring it to some resolution. There was a woman I had loved and lost. Not that Nichole had ever loved me (except, I believe, as a friend). What I had lost when she left the States was the joyful agony of seeing her face by candlelight over the occasional dinner while hearing her stories of her vibrant Italian kin. As her replies to my letters grew less frequent, I realized that even that last insubstantial literary contact was fading into absolute absence. On my long bus ride north to Eryri, I reached out one last time, wrote to her of Avebury and posted the letter at the next stop.

The name on the return address struck a pang through me. I tore open the envelope. Nichole, perhaps because my tale was so odd, had replied. She gave me a London contact number for one Reverend Sam Stock. Owen, she wrote, I want you to talk to this man. He deals with things that you and I were taught to believe cannot be, but are, anyway. Nature is so inconsiderate that way. Sam is a good guy. He was trained by the Berkeley Psychic Institute. Don’t worry, they aren’t like those telephone ‘psychics’ with bad accents you see on late night commercials. I trust Sam because he helped me. When my plane was flying in to London, I had a sense of coming home, even though I have never been here before, and a sense of misease at the same time. As soon as I set foot on English soil, I felt an awful pain in my back. I thought for a moment I had been hit by something, but I hadn’t. It wouldn’t go away, and it was hard even to walk. It went on for days, until Sam came to London to visit Bob and It’s too bad you can’t come see some shows with us, but our schedules just wouldn’t mesh… Rev. Stock met me at dusk outside the empty church in the great circle of Avebury. I am not sure what I expected, but it was not this man. Stock was blond, bland of face and build. His eyes never seemed to focus on anything around him, because he was always focused on things just past the surface, things I could not see. We introduced ourselves and he cracked crude jokes and laughed at them, establishing his credentials as a normal guy in all things but his specialty. “Shall we go in?” he asked. I nodded, opened the wide church doors and led the way into the deep gloom. We made our way carefully to the spot where I had lain. The brass silhouette of the knight was barely visible as the last light receded behind heavy November clouds. Sam did not produce a flashlight. That made sense, I supposed, as there was nothing really to see. Sam spoke calmly of relaxing. We sat on the stone floor and let the darkness deepen, keeping our minds clear. I do not know how long we sat there, Sam exercising his psychic disciplines, whatever they may have been, and me drifting into semi-dreams, then starting back to normal consciousness, trying to empty my mind, and drifting again. Then the presence was there, pressing at me, trying to drive me away with wave after wave of palpable hostility. Sam spoke quietly to it, asking, “Why are you here?” The Reverend sat very still, drawing in some response. “That’s not it,” he said. “Look deeper.” I winced, as a wave of horror hit me, suffused me. Terror shook me, body and soul. Images flashed through my mind: a village in a grassy hollow, remote, isolated from the larger world, steeped in ancient ritual. A knight in dully gleaming armor restrained his restive war-horse, looking down on the village. Lances bobbed and weaved on either side of him and distant glints of steel flashed here and there on the hills beyond the village — the settlement was surrounded. The nameless knight watched a man in long robes, his care-lined face stretched thin with sorrow and fear, trudge out from the village to stand before an incredibly broad, stocky knight on an irritable charger. I could not make out the actual words, but I understood that this stocky commander’s troops had been sent by some distant religious authority to enforce conformity to their sect. The long faced man tried to explain that the villagers’ creed joined them in spirit with the land on which they dwelt, The whole village had met in council. They understood what the invading church meant to do to any who resisted, but the village had decided as one that it would be better to die as one with the land, than to eke out a spiritless survival as serfs to those who betrayed the trust of ages. The stocky commander was unconcerned. He let the old man walk all the way back to the village. The stocky man calmly drank a stoup of wine, then tossed the flagon to his page and sent him behind the lines. The commander flung up his metal sheathed hand and… All hell was loosed. The knights rode down any they found in the streets. They spitted men and women, while the foot soldiers tore down doors and slaughtered cattle.

A small child ran through the streets, heart pounding, breath catching, running blind. Steel clattered behind him, torchlight flamed, a huge, steam-breathed horse cut off his path. Terror jangling every nerve, the boy darted through an open door into an abandoned home. Coals and dying flames in the hearth cast wavering light on an empty bed. The boy dived under it, huddled against the wattled wall, looking back the way he had come. The jointed metal gauntlet reached down from the towering figure, seized a thin arm, yanked the child up and flung him to the floor. One iron boot came down on a small shoulder, pinning him. The great gauntlet flexed its metal joints, reached to the knight’s belt and drew a dagger. The knight knelt, faceless in the wavering light, aiming the dagger-point at the boy’s belly. My limbs quivered and jerked as wave after wave of horror crashed through me — a tidal wave of terror and dismay so sweeping that I was screaming without inhibition. Shockingly bright after-image colors flared in my eyes and the village was gone. I was back in the church with Sam. I was not cut open, not a child, not screaming, only shivering a little in the dark. Sam was talking calmly with the presence, the nameless knight. “It was one thing,” Sam was saying, “to get caught up in the collective madness. It was something else to live with it. Isn’t that right?” There was a pause while Sam listened and I gasped, willing my hammering heart to slow. Unseen in the dark, Sam addressed the knight again, “Your leaders told you that you were absolved from any crime you committed against unbelievers. But you knew better. That night haunted you all your life. Especially the face of the screaming boy. Then you died. And you knew where damned souls go. You didn’t dare pass on, did you? You stayed here, stuck in the floor of the Avebury church, hiding from judgment behind other people’s

“Get out of my head,” I muttered angrily. Sam told the knight, “Stop that. We’re not interested in any death imagery you can throw at us. I’ve had worse, “I won’t give in,” I told the presence. “I didn’t give in then. I’m not a child anymore and no violence, no oppression, no cruelty has ever made me conform. I won’t get out. You see that child’s face in me? As long as you and I are in this world, you’ll see it still. Face me — I can face you.” Sam spoke to me this time. “He’s stuck. Time isn’t the same for him, but still, he’s been here too long. He’s a weak character or he never would have done those things. He can’t go on unless you give him the power to do it.” “What do you mean?” I asked. “If you forgive him, his hold on this plane will weaken, and scared or not, he’ll eventually lose his grip and move on to face the consequences of what he’s done.” “Forgive him,” I repeated, incredulous. “Or you can not forgive him,” said Sam dispassionately, “and he’ll stay stuck here as the centuries go by.” I took a breath. “You pitiful monster,” I said, “six hundred years is long enough to be stuck in a church floor. You wasted one life being weak and vicious. The only way you’ll ever redeem yourself is to live again. It’s not up to me to even this score — it’s up to you. I forgive you. Go on to your next life. And do better.” The dread eased. There were no more ugly images, no pressure to leave. The sense of a presence dwindled. He was not yet gone, but his hold had been weakened. He receded to absorb what had happened. After a moment, Sam said, “He’s still afraid to go on. He knows he hasn’t paid all his dues yet. You’re the only person on this plane he can contact, and the only connection he has with you is terror, so it may be pretty unpleasant. But you can comfort yourself with the knowledge that sooner or later, he’ll slip away. We might as well go, too.” We groped our way to the doors and slipped out into the night. Sam shook my hand. “That’s really all I can do for you,” he said. I thanked him. He gave me his card, adding, “Sometimes I give classes. Look me up sometime when you get back to California. Or forget the whole thing, if you’d rather.” “Thanks again. Give my love to Nichole.” Sam hesitated just an instant, just enough that I knew he was aware of my doomed love and that he would not be passing on any expressions of affection when he spoke to Nicole. I nodded and he walked to his hotel room while I hiked out to my hedge.

The day after my arrival, the phone rang. It was Ambrose Douglas, an actor with whom I had once worked. He told me, “I’m working at the Robert Semple Theater and I told them you’d be perfect for this part. It’s not much money, but it’s a good role and a good company.” “It’s a start,” I said. So if that time comes to you — if you hear the road call your name because you feel that if only you can drive far enough, there’s somewhere you will arrive — I can tell you: so you will. When you’re lost at sea, remember: if there’s no way to keep your foundations solid rock, there’s no sea either without shores.

|

![]()

Winter Solstice: The Unconquered Sunby Jane Shotwell

|

Winter Solsticeby Dr. Jean Shinoda Bolen

|

Winter Solstice

|

|

“If you’re reading this post before lunch, be prepared to work up an appetite–or at least a very strong craving for salmon! Today J.S. Dunn is here to talk about what a winter solstice feast would have been like in ancient Ireland. I’m fascinated by this for several reasons, but not the least of which is that I’d been led to believe that the ancient Romans and Greeks didn’t use butter, using olive oil instead. If the ancient Irish were using butter, I wonder what accounts for this difference in ancient culture? Read on for a delicious recipe on a Juniper Reduction!” ~ Stephanie Dray

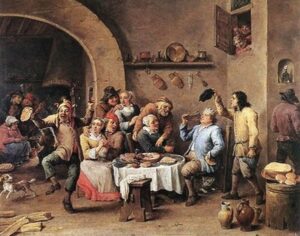

Food is important in Bending The Boyne for a number of reasons. Ireland What did the ancient Irish eat at 4,200 years ago? And, what about the peoples in what is now Portugal/Spain, the Costa Verde, and up the Bay of Biscay to the Loire/Morbihan coast? At first, researching prehistoric foods for this tale looked daunting. The Dindshenchas, the medieval text that provided myth fragments for Bending The Boyne, has clues to the early diet: the sacred salmon of knowledge, the hazelnut which also imparts wisdom,cereal grains for porridge, and various berries. The ancientsused milk and butter from their herd animals. To this day, well-made oak casks holding Bronze Age butter turn up at digs in the bogs. Domestic meats of sheep and cattle, and cuts of wild deer and boar, show

An ancient prohibition on killing swans, a geis, provided material for the plot. There is evidence that swans were indeed eaten for food, and swans winter at the river Boyne in great numbers. The prohibition re: swans was perhaps politically motivated—this novel shows a plausible reason for that geis. The ancients’ knowledge of edible seeds, roots, and herbs would far exceed our own based on paleobotany surveys at excavations. They collected and dried the wild apple in the Isles, and berries. In warmer latitudes like ancient Spain the Bronze Age people began to cultivate the olive and other fruiting shrubs. There is evidence they knew which acorns to collect, and ground those into flour. Spain’s meltingly tender acorn-fed ham shows up in this novel, for that may have begun in antiquity given their early use of abundant acorns. Ultimately many passages about food became a joy to write to show the richness of the environment for those who well knew how to utilize it. For these ancients, a feast probably was literally a sacrament of life. The reborn winter solstice sun showed the ancients that spring’s bounty would return.

Boyne Solstice Feast

* From Welsh myth, Song to Mead Juniper reduction sauce for modern roast wild game: Here is a simple (and relatively low-fat) reduction sauce if you Roast or sauté the meat, keep warm. Deglaze the pan with around

J.S. Dunn lived in Ireland during the past decade, on 12 lovely acres Bending The Boyne reflects the new paradigm that Gaelic culture Amazon B&N |

![]()

A Leaf from the Tree of Songsby Adam Christianson

|

The Shortest Dayby Susan Cooper

|

Hymn to UbellurisGenerously contributed

|

|

Ubelluris, You hold

Ubelluris Ubelluris,

©2011 |

![]()

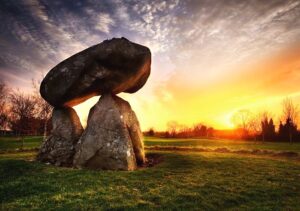

A Brief History of the Celts (Ireland)Generously contributed

|

|

In today’s society, we see Irish art, dance, and food, but

References: |

![]()

The Three Fires |

|

We acknowledge the Three Fires First, to the spirits of the land and this place; We acknowledge the second fire:

We acknowledge the third fire: To the Three Fires—may we kindle you at all times, and

~~ Source Unknown ~~ |

![]()

Water on Water’s the Wayby Alison Leigh Lilly(Used with permission)

|

To Step into the Fire |

|

The land of dreams,

~~ Pippa Bondy ~~ |

![]()

Dispatches from RDG’s

|

|

Mother Grove of the Reformed Druids of Gaia Eureka, CA: Sybok has spent many hours over the past few months revamping the RDG and OMS websites using the Drupal software. The RDG site is much more Sybok is also in the process of creating a new site for the Hasidic Druids of North America. We note that this year, the first night of Hannukah coincides with Solstice night. The Mother Grove will be getting together at the Archdrud’s home on the Solstice for Water Sharing and the eating of cookies, cakes, and other goodies. And next year in Dryad’s Realm! In The Mother Grove is the home of the Senior Archdruid of RDG and of the Patriarch of the Order of the Mithril Star.

Colorado Springs, CO: Current plans to take place this next year is to work with our land and how this is to be is unsure as of yet although we trust that Dalon ap Landu will lead the grove in the right direction. Even though slumber is imminent, the Arch Druid intends to keep the tradition to make pilgrimage of Drumming Up the Sun at Red Rocks Amphitheater, in Morrison, CO, continues as it does every year will be held We look forward to a long winters rest as it is time to go forth deep in the bosom and love of the Earth Mother. From our grove to yours, Blessed Calan Gaeaf and a Merry Alban Arthuran

Agoura Hills, CA: We enjoyed dessert and conversation after ritual and watched We will present a Winter Solstice ritual at and with the local Our activities are listed on Witchvox and the L.A. Pagan Examiner. MYNT,

Swansea, Wales, U.K.

Spokane,WA That’s the new from Polaris Grove in lovely Eastern Washington! MYNT,

Bullhead City, AZ Brightest Blessings & May You Never Thirst,

RDG ProtoGrove, Crossville, TN: Our online Family

Middleburg, FL: Till

Anderson, CA: Blessings

Although it’s not a “Grove”, the NoDaL still qualifies as an “autonomous collective” of the Reformed Druids of Gaia, and consists of all the 3rd Order Druids therein. The purpose of the NoDaL is to provide a space for Archdruids of the RDG Groves and Proto-Groves to discuss the many aspects of running a group of Druids, and provide advice and support for each other. They also act as the “legislative” branch of the RDG – creating policy as needed. In January 2011, the NoDaL voted to make some changes to the degree

Philadelphia, PA: Looking to our ancestors and the ancients, Aelvenstar Druids respect all life and receive inspiration from Nature and the heavens. We believe it is the natural state of Mankind to live in harmony with Nature. and that it is our responsibility to respect and protect the Earth. As activists, it is our responsibility to do our part collectively and individually to heal the environment. Emphasizing development through the practice of Druidcraft, focus is placed upon personal growth through the development of body, mind, Aelvenstar Grove holds eight celebrations a year, on the solstices, equinoxes, and cross quarter festivals. We sometimes meet on other occasions for outings and initiations. Online meetings and initiations are held too, as some members live a distance away. We welcome new members of all backgrounds who love nature and seek Courses available: Reformed Druidism 101

Live Oak , FL: Blessings,

Roots Rocks and Stars Albany, OR:

|

![]()

|

Seasonal Almanac

|

![]()

The State of the Reform

|

|

Being the 6th Year of the 2nd Age of the Druid Reform

|

|

As of today 668 Druids have registered with the RDG: During the Fifth Year of the Gaian Reform, we experienced a net registration gain of 38 Total Groves chartered: 4 Our oldest Druid is 79 years old. |

![]()

![]()

The Druids Egg — 1 Geimredh YGR 06 — Vol. 10 No.1

NEXT ISSUE WILL BE PUBLISHED ON

Imbolc – 1 Earach YGR 06

WANT TO JOIN THE REFORMED DRUIDS?

http://www.reformed-druids.org/joinrdg.htm

WANT TO DONATE TO THE REFORMED DRUIDS?

http://reformed-druids.org/donate.htm

![]()

Published four times each year by The Mother Grove of the

Reformed Druids of Gaia

Cylch Cerddwyr Rhwng y Bydoedd Grove

Ceridwen Seren-Ddaear,

Editor-in-Chief / Webmaster

OMS Patriarch Sybok Pendderwydd

Eureka, California USA

“An autonomous collective of Reformed Druids”

Copyright © 2011

No portion of this newsletter may be reproduced by anyone for any purpose>without the express written permission of the

Editor-in-Chief, Ceridwen Seren-Ddaear, Senior Archdruid, RDG

![]()

![]()

All images are believed to be public domain, gathered from around the internet over the years. and/or sent to us by friends. However, if there is an image(s) that has copyright

information associated with it and the copyright holder wishes for it to be removed,

then please email us and we will remove it. Or, if any of the artwork is yours and you

just want us to give you credit (and the piece can remain on site), please send us your link/banner and we will be happy to do so.

![]()

The Druid’s Egg e-zine is supported by our online store:

![]()

The Mother Grove wishes all of you

a most prosperous Samhain, an abundant Yule,

and many blessings throughout the season!

“

“

–

–