I remember a former nun who came to me in southern California for

a past life session back in the 1980’s. We sat talking at first,

getting to know one another, and she told me about an experience

she had had just before leaving Los Angeles to drive up to my

place.

“I invited a priest-friend of mine over for breakfast this

morning,” she said. “He was making himself a cup of

coffee and I said, ‘Guess what I’m doing today.'”

“‘I have no idea,’ he said, and he poured boiling water into

his cup of instant coffee.”

“I’m driving up to Oxnard to be regressed to a past life.

Do you believe in past lives, Father Jim?”

“‘No,’ he said, calmly stirring his coffee. ‘But then,’ he

added, looking me straight in the eye, ‘I didn’t believe in them

my last lifetime either.'”

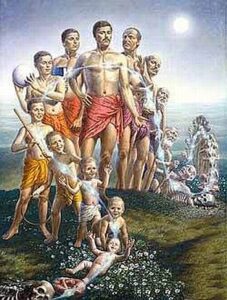

A past life is simply a life you lived before your current life. You lived it in a different body, often a different gender, a different race, with different parents and friends, different dreams and beliefs, different priorities, different skills, different loves, hates, and fears. Were you to meet that earlier “you,”

A past life is simply a life you lived before your current life. You lived it in a different body, often a different gender, a different race, with different parents and friends, different dreams and beliefs, different priorities, different skills, different loves, hates, and fears. Were you to meet that earlier “you,”

you might not recognize yourself. Nevertheless, some of the physical and psychological makeup of that earlier “you” remains subconsciously influencing you today, for good or ill, just as you will influence your future lives.

Some people can tune into their own past lives unaided. They might

experience them in dreams, meditation, or through travels that

suddenly stimulate past life memories. If you have never had such

experiences and do not know someone who can act as a facilitator

in unearthing past lives, you can still find many hints about

your earlier lives through things that fascinate you. A love for

certain kinds of ethnic music, for example, is a strong indicator

of the peoples you once lived among. Your taste in clothing and

jewelry is another indicator. A love of silks might suggest lives

of wealth in China or India. A preference for simple styles and

fabrics could indicate that you have lived happy lives close to

the earth. If you often dress in severe, unattractive, dark clothing,

a past life as a nun or monk might be guiding such choices because

of the safety and protection they once provided. Flamboyant clothing,

bright colors, gypsy flair, tinkling jewelry, all point to more

dramatic lives, enriching society through the arts but often lived

on the fringes. The possibilities are endless.

If you have unexplained fears without a current life basis, these

fears are another source for tuning into past lives. Fear of drowning,

burning, starving, or being buried alive are among the most common

fears but there are many others. Wounds can be indicators too:

if you died of a specific wound in an earlier life, your current

body might be marked by illness or an increased sensitivity at

the site of that earlier death-wound.

All such experiences from a past life, whether positive or negative,

have the potential to influence a current life. Tuning into the

root cause in a past life might not disconnect the influence —

sometimes it is too deeply embedded in body and psyche for that.

But at least it may help you to understand where it comes from

and this, in turn, may gradually soften any discomfort.

Why Would We Live More Than One Life?

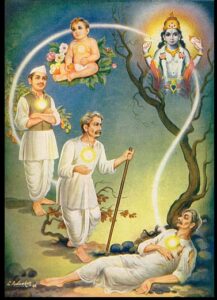

It is said that we need all these varied experiences and roles to be whole. Another way to approach this is to say that we only live one life, but in many different bodies and circumstances. We might say that we are like a kaleidoscope filled with thousands

It is said that we need all these varied experiences and roles to be whole. Another way to approach this is to say that we only live one life, but in many different bodies and circumstances. We might say that we are like a kaleidoscope filled with thousands

of different pieces of colored glass, all coming together to create an endless array of beautiful patterns. Or we could compare our past lives to beads on a necklace; each bead is handmade, unique in its own right, but also part of a larger whole.

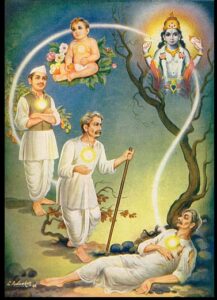

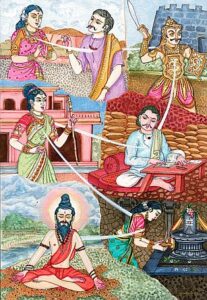

According to the theory of reincarnation, we live many lives in

order to accumulate wisdom and compassion in multiple layers of

experience. Answering the needs of others as well as honoring

our own, for example, takes many lifetimes of trial and error.

In some of those lifetimes, you might be a healer, a nun, a loving

parent, or a spiritual leader, learning to put the needs of others

before your own. But sometimes you learn to do that so well that

you become totally one-sided, so self-sacrificing that you completely

neglect your own needs, feeling selfish even if you think about

them.

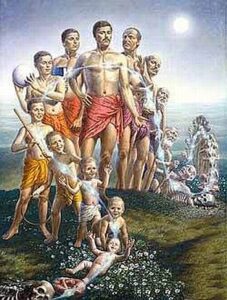

The soul cannot tolerate such one-sidedness for long and eventually

you will find yourself in lives where you might be consumed by

the arts, driven to put the expression of your own creative soul

above more practical considerations. Or you might find yourself

born as a disabled child, forced to be vulnerable and to let others

care for you, as you once cared for them. Finding a balance between

living out of one’s egotistical drives and expressing one’s genuine

soul-yearnings is a delicate and often excruciating process. If

you have been self-effacing for too many lives, you may no longer

be able to tell the difference between being selfish or not. Then

you may need to deliberately do what feels like being “selfish”

in order to re-set the inner balance-wheel.

Another difficult area involves courage, for there are many kinds

of courage. In one life, you might be a warrior learning about

courage in battle. In another life, you might be a farmer’s wife,

equally learning about courage in the face of unpredictable weather,

poor crops, an exhausted husband, and sickly children. In yet

another life you might learn about courage by fighting political

corruption and oppression. A child knows courage, so does a homeless

person, a refugee, a terminally ill person. If we are not to get

stuck in a one-sided “hero” definition of courage, we

have to understand all its many and complex dimensions, not by

reading books about it, but by living it.

Learning to love, to be compassionate, to genuinely desire that

all beings, all life forms, be shown kindness — this take countless

lifetimes — and yet mastering these energies are the most important

of all, for they are what makes us truly human. As Gandhi wrote

about love:

If for mastering the physical sciences you have to devote a whole

lifetime, how many lifetimes may be needed for mastering the greatest

spiritual force that mankind has ever known?

Getting Stuck in Archetypal Roles

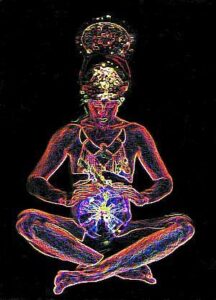

We rarely know that archetypes exist unless something happens to activate one. Even then, most people do not understand what has been activated or what it means. An “archetype” can perhaps best be understood as an energy-field within the psyche.

We rarely know that archetypes exist unless something happens to activate one. Even then, most people do not understand what has been activated or what it means. An “archetype” can perhaps best be understood as an energy-field within the psyche.

It is a “field” with no content — in other words, it

comes without any images or emotions. It is a very powerful energy-pattern, however, and if a specific image or emotion enters its range and adequately matches its abstract structure, the archetypal field will grab onto that content and “fix” it into place as an expression of that archetype.

Sometimes this process is culturally specific — in India, for

example, Kali might represent the Divine Mother archetype, while

in the West the Virgin Mary might embody that same role. But archetypal

and karmic patterns are often intricately interwoven, which means

that some of the archetypes in an individual psyche may carry

an intense karmic “charge.” Thus the Divine Mother archetype

for some individuals might be embodied by a living woman known

to them from earlier lives — a spiritual teacher, perhaps, or

a loving relative.

There are countless archetypes within the psyche. Greek and Roman

deities are the most familiar representations of them in the West.

This does not mean that these deities are archetypes in and of

themselves. It only means that they carry a power or energy that

allows them to function as “content” to otherwise contentless

archetypes. The Roman war god Mars, in other words, is not an

archetype, but he represents what the warrior archetype is all

about. Unfortunately, for several thousand years, this archetype

has been attracting highly addictive contents. Once this archetype

is activated within the psyche, the warrior’s path may exert such

an intense fascination that everything else pales around it. We

no longer worship Mars, of course, but the reincarnations of many

of Rome’s finest are with us still and any sufficiently charismatic

general might easily carry an archetypal “charge” strong

enough to persuade his troops to follow him even into the most

hopeless of battles. Such warriors die, tend to be swiftly re-born,

and fifteen to twenty years later they are likely to be serving

as warriors all over again — unless circumstances allow for the

intervention of a more benign archetype.

Venus also is not an archetype but she shows us what the Lover

archetype is all about — if a Venus-like beautiful woman activates

this archetype within us, we may experience the heights of bliss

but also the depths of folly. Her relationship with Mars creates

special psychological difficulties.

Hera and Zeus are not archetypes either but we can understand

the Royal Leadership archetype by studying how they use and abuse

power; if something activates this archetype within our psyches,

we may find ourselves playing out their mistakes before we realize

what is happening.

The Greek myth of Persephone models for us the anguish of the

Raped Maiden archetype just as her mother Demeter reveals the

depths of the Sorrowing Mother archetype. Many women who have

experienced firsthand either or both of these realms find profound

consolation in the stories surrounding these two goddesses, for

they offer a way through horror to the promise of a mysterious

healing source within the psyche.

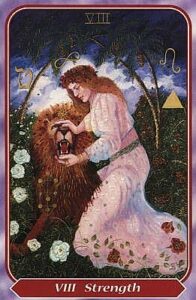

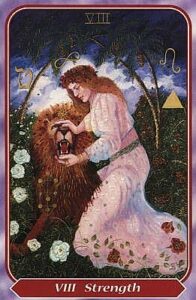

The twenty-two cards of the Tarot’s Greater Arcana are another source

The twenty-two cards of the Tarot’s Greater Arcana are another source

that provides examples of what goes on behind the scenes in the

underlying archetypes we recognize in the images of the Magician,

the High Priestess, the Emperor, the Empress, the Hermit, Death,

the Devil, the Hierophant, the Lovers, and so forth. Like all

contentless archetypes, they are value-neutral: they can nurture

us and give us great gifts of wisdom and insight, but if we identify

too strongly with any of them, we can also wind up being possessed.

Honoring one to the exclusion of the others is unwise.

Similarly, a careless dishonoring of any of them is unwise. The

patterns each of them represents are hard-wired into our psyches

and can no more be dislodged than our blood vessels or neural nets.

As mentioned in the above section, “one-sidedness” is

the clearest sign that one has been gripped by an archetypal energy,

or role, with which one was probably over-identified in the past.

We all know insecure comedians who are always “on”;

cloyingly charming Southern Belles; smug fundamentalists who are

unrelentingly “right”; and males who are defined solely

by their arrogant machismo. These people are so one-sided that

they seem like caricatures. They are so caught up in a single

role that it is difficult to relate to them on a human level.

Here are a few other examples of what getting caught in archetypal

energy might look like…

A male who refuses to mature is called a Peter Pan, or puer (an

Eternal Boy). Part of this refusal to mature is cultural, for

the West worships youth, but when such a trait manifests in an

individual male, it could come from a life in which he died young

and never had a chance

to grow up. In later lives, he might cut off his psychological

maturation at that same point. This becomes his way of holding

onto a life he never got to live. Unfortunately, the aging Peter

Pan (or what I call a “wrinkled puer”), does not get

to live either — his life becomes a stale mockery of youth.

Imperious types, whether male or female, express the Emperor/Empress

role, which could stem either from wishful thinking or from an

actual royal life that needs to be released in order for them

to more gracefully rejoin the human race. These are the people

who say, “You’re either with me or against me.” They

expect their relatives and other minions always to agree with

them, praise them, and flutter around them. They become quite

unpleasant, even dangerous, when this does not happen. The “charge”

of the archetypal energy they carry is often quite capable of

constellating a disaster or crisis designed to keep them in power.

Along the way, they often retreat into psychological “bubbles”

and disown disobedient family and friends.

The “saintly” archetypes such as teacher, healer, and

priest-minister-rabbi-guru are notoriously easy to get caught

in. These can be beautiful, nurturing, and necessary roles, but

if we get so trapped in them that we have no life of our own —

and our mates (like C.G. Jung’s wife) are forced to manifest our

own unexplored shadow sides by becoming increasingly bitter and

bitchy — then we need to look at those earlier lifetimes where

we first got trapped, and, again, as with Emperor/Empress, find

ways to rejoin the human race.

If thinking of archetypes as force fields seems too abstract,

another analogy would be to think of the psyche, first, as a vast,

interdimensional ocean mysteriously held within the “leather

bag” of the brain (actually, psyche isn’t limited to the

brain — it’s throughout the body, but it’s simpler to think of

it as living in the brain). Within that ocean are archetypes —

think of them as a patterned potential for “riptides.”

That potential may only rarely be activated.

Let’s use the example of a riptide for the Hermit archetype. This is

Let’s use the example of a riptide for the Hermit archetype. This is

a very valuable and healing archetype but it isn’t currently functioning

in as widespread a manner as the Warrior or Lover archetypes.

If you read the luminous writings of Thoreau or the Trappist monk,

Thomas Merton, you may be deeply impressed with the value of living

in a solitary hermitage and communing with nature or a chosen

deity. This may lead you to respect the Hermit archetype but it

doesn’t necessarily mean it will be activated in your own life.

The riptide potential of this archetype will only be activated

if the archetype is interwoven with your own karmic patterns.

This might involve a deep longing for such a life born in a past

life. More likely, it will emerge from your actual experiences

lived as a hermit in earlier lives. Then, it is as if a riptide

reaches out of nowhere, capturing the emotions, memories, and

images, and gripping you so strongly that you leave everything

behind and go off to live in the wilderness. Being gripped by

an archetype can be exhilarating and blissful. One can be a hermit

and reach immense psychological depth and maturity. In this case,

the karmic activation of that riptide was your destiny and highest

good.

But this can be very tricky. If you, in your earlier hermit lives,

already fully experienced the demands, challenges, and rewards

of that life, then to return to being a hermit would be at best,

nostalgia, and at worst, an escape. If the choice is not born

from a genuine desire for growth, the archetypal energies become

destructive. You then lose your footing, your sense of humor,

and your psychological flexibility. Although you may hide this

from others, even from yourself, you will become increasingly

rigid, cold, and misanthropic.

Bottom line: any time we are caught up in an outgrown archetype,

no matter how compassionate and caring it might seem on the surface,

it makes us one-sided and our lives become obsessive. When this

happens, the root of the problem probably lies in an earlier lifetime

where we identified too strongly with the archetypal energy of

a given role.

In such circumstances, exploring our own past lives, not only

to find the obsessive root, but also to explore the wide range

of alternate roles belonging to our own karmic palette, is highly

recommended. Other options include reaching out to alternate archetypal

energies and “wooing” them by taking up new interests

and widening our circle of friends to include those who have already

mastered “roles” we need for our own completion.

For psychic health, one needs to dance with, or at least be on

speaking terms with, a wide variety of archetypes. To overly identify

with one is a clue that one is stuck and unable to grow except

in that one direction, until ultimately one topples over. Just

as the human heart rate is healthiest when it is flexible and

variable (it is locked into a rigid, steady beat only when death

nears), so too the body and psyche need to embrace many flexible,

variable roles.

Why Bother to Explore Past Lives?

If we have had past lives, we have also obviously had past deaths.This fact is a major reason why people are interested in exploring their past lives — it places the inevitability of death in a much larger context and makes it far less fearsome. It also gives

If we have had past lives, we have also obviously had past deaths.This fact is a major reason why people are interested in exploring their past lives — it places the inevitability of death in a much larger context and makes it far less fearsome. It also gives

us the hope that when those we love die — whether a family member,

a close friend, or a beloved pet — we will meet them again and

once more share the joys and sorrows of life. We will continue

growing together, laughing, being kind to one another, fighting,

making up – exploring all the nuances of possible relationships.

People may also wish to explore past lives to re-discover skills

they once had, for these can often be reactivated and become a

new line of work, or a cherished hobby. Looking into the past

for root causes of illness or unexplained fears is another important

reason for past life work.

Next to reducing the terror of death, however, the most frequent

reason people desire to explore past lives

is to understand relationships better. Close,

loving relationships never happen by accident — they emerge out of centuries of experience with that other soul. The same can be said of difficult, painful relationships — these too always have a long history. Knowing that history can help us to better understand the deeper issues, allowing either for a long overdue

truce or for a permanent “divorce” if the relationship is too toxic to be salvaged, at least in this current lifetime. Knowing the history of the animosity gives us the clarity and distance to see the wisest course of action. That deeper context allows our choices to come from wisdom, not anger or despair.

Perhaps the greatest benefit to be derived from exploring past

lives comes from a growing sense of serenity and trust in the

process. There is often great pain and confusion in our lives

and we may often feel our lives are meaningless. But when one

explores the complex and often wondrous patterns in the past,

things begin to fall into place and one slowly understands that

a larger mystery is unfolding. As British playwright Christopher

Fry wrote in his The Dark is Light Enough:

There is an angle of experience where

the dark is distilled into light:

either here or hereafter, in or out of time:

where our tragic fate finds itself with perfect pitch,

and goes straight to the key which creation was composed in….

Groaning as we may be, we move in the figure of a dance,

and so moving, we trace the outline of the mystery.

Perspectives on Exploring Past Lives

also by Kathleen Jenks, Ph.D.

There are many ways to begin an essay on reincarnation. I could write

about ancient burials in Siberia, where, as Joseph Campbell documents,

the body was colored with red ochre as a sign of life’s blood

and then buried in a fetal posture, facing east — an indication

of a belief that the dead would live again like the sun, rising

again in the east. I could also write about the males of Aboriginal

tribes in Australia who sing the spirit of an ancestor back into

a woman’s womb. Or I could mention that the ancient Celts accepted

reincarnation as such a normal part of life that loans were made

based upon repayment in a later embodiment. Such beliefs in rebirth

are common, and the majority of earth’s non-monotheistic peoples

take them seriously. Gandhi, for example, wrote eloquently:

If for mastering the physical sciences you have to devote a whole

lifetime, how many lifetimes may be needed for mastering the greatest

spiritual force that mankind has ever known? 1

India, of course, is well known for accepting reincarnation. The

very word karma, which could be loosely translated, “as you

sow, so you shall reap,” comes from India. What is less known

is that the concept of reincarnation was also openly embraced

by one of the framers of the American Declaration of Independence,

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790). When he was twenty-two, he wrote

his own epitaph. It was never used on his gravestone but it reflects

a viewpoint he held the rest of his life:

The Body of B. Franklin, Printer,

Like the Cover of an Old Book,

Its Contents Torn Out

And Stripped of its Lettering and Gilding,

Lies Here

Food for Worms,

But the Work shall not be Lost,

For it Will as He Believed

Appear Once More

In a New and more Elegant Edition

Revised and Corrected

By the Author. 2

When Franklin was eighty, he wrote a friend, “I look upon

death to be as necessary to the constitution as sleep. We shall

rise refreshed in the morning.” Between Gandhi and Franklin

lie vast numbers of Western philosophers, poets, authors, artists,

and thinkers from all walks of life who have shared these beliefs.

People who are in touch with their own creativity are especially

likely to resonate with concepts of reincarnation because their

very creativity is a mystery of unknown origins. Thus, seeking

those origins in one’s own memories of earlier lives has its own

logic. Pythagoras advised souls returning to rebirth to beseech

the Goddess of Memory, Mnemosyne, to let them keep their memories

by allowing them to drink of her spring waters. Mnemosyne is the

mother of the Muses — in other words, she, as the Goddess of

Memory, is the font of all art. She can give us knowledge of beginnings,

origins, and earlier times because she remembers all the winding,

interconnecting stories.

According to Plato, when we die, we drink of the waters of the

river Lethe, which washes away our memories of the life just lived.

“The dead,” Mircea Eliade writes, “are those who

have lost their memories.” 3 But in another sense, the dead

are in the midst of experiencing celestial realms and garnering

even more memories. When they return to life, they first leave

the underworld by way of the left-hand road that goes to the spring

of Lethe and, “gorged with forgetfulness and vice,”

according to Plato, they drink the waters and their celestial

memories are lost. So the living are also those who have lost

their memories.

Pythagoras advised his followers not to take the left-hand road

to Lethe, but to go to the right instead, and find the road leading

to “the spring that comes from the lake of Mnemosyne. ‘Quickly

give me the fresh water that flows from the lake of Memory,’ the

soul is told to ask the guardians of the spring.” 4 That

soul, its memories intact, is then reborn as a great master.

The Buddha is said to have argued that “Gods fall from Heaven

when their ‘memory fails and they are of confused memory’.”5

Gods who don’t forget remain eternal and unchanging. From this

perspective, to forget is to fall from heaven, which gives an

interesting nuance to the myth of Lucifer in the West — and to

the “Lucifer” within us. Some people say, “the

devil made me do it.” From this Fall-equals-loss-of-memory

perspective, that’s exactly right. The loss of memory, the loss

of awareness of other choices and repercussions, pushes us into

repeating similar mistakes over and over. We fall.

Eliade comments:

…Knowledge of one’s own former lives

— that is, of one’s personal history —

bestows…a soteriological knowledge and mastery over one’s destiny….

That is why ‘absolute memory’ — such as the Buddha’s, for example

—

is equivalent to omniscience…. 6

That’s a very male way of looking at it, of course, in terms of

mastering one’s destiny, getting untangled from karmic burdens,

and returning to the celestial heavens. That may indeed be  what

what

it’s about for many, but I’m not sure that’s all there is to it. Having a body is a precious gift, one to be valued and lived in tenderly, anointing it, allowing quiet joy to be flowing in cell-deep pools, filled with their own memories. The body is a companion,

not a servant, and, in my view, each body we inhabit leaves an indelible imprint upon the soul. How could it be otherwise, when both are so interconnected, when matter itself is understood as a different vibration of spirit?

So in exploring past lives, we go into the Place of Memory, to

her lake, her springs, her fountain, and drink of those waters

and ask for gift of being able to remember.

Over thirty years ago, my personal experience in a past life regression

session facilitated by the late Marcia Moore convinced me of the

value of exploring what seemed to be memories from ancient times.

I began facilitating past life work shortly thereafter, and have

continued to do it all these years, because I believe that by

healing one’s personal past we contribute to a wiser, saner present.

British playwright Christopher Fry wrote in his The Dark is Light

Enough: is an angle of experience where the

dark is distilled into light:

either here or hereafter, in or out of time:

where our tragic fate finds itself with perfect pitch,

and goes straight to the key which creation was composed in….

Groaning as we may be, we move in the figure of a dance,

and so moving, we trace the outline of the mystery.

Exploring past lives is a way of tracing “the outline of

the mystery.” It can be seen as a ritual of time-travel,

a journey into imaginal space, or a journey into the personal

unconscious. It is through such underworld experiences that we

explore what Christine Downing calls “the times of real soul-making.”

7 The work can be called past life regression, story therapy,

far-memory exploration, active imagination, or guided meditation.

The exploration can be viewed as a literal exploration of an earlier

lifetime, but it can also be interpreted in terms of metaphor,

an “as if” adventure, a theatre-of-the-mind, a tapping

into Jung’s “collective unconscious.” Jean Houston calls

such a process, simply, an “intellectual focusing technique.”

Regardless, it’s a way of letting yourself be drawn back into

an ancient life or “story” that is especially rich in

personal relevance for you.

No matter what we call it, the memories are there and most people

No matter what we call it, the memories are there and most people

can access them in light trance states with full conscious awareness of the process. Belief is not important, nor is one’s personal philosophy. Despite one’s intellectual belief system, we hold within us many worlds, many ages — some tranquil, others full

of drama and passion. Whether we call it soul-work or nonsense,

the memories and emotions are there, influencing us not far below

the surface. We feel them like a fleeting joy — or like the pain

of a phantom limb. In a sense, it’s like childbirth muscles: all

women have them but they’re rarely used more than three or four

times in an entire lifetime, and sometimes they’re not used at

all. Yet they’re still there.

So it is with the “muscles” of these memories, these

stories. If one chooses to explore them, it’s important to set

aside any bias in order to do “fieldwork” within one’s

own mind. Specialists educated in specific disciplines are often

the easiest to regress, for they are trained to bracket-out preconceptions

in order to simply deal with a phenomenon as it presents itself.

But everyone has the natural ability to access these “muscles.”

All one has to do is to stay open and see what emerges. If the

experience gives a new perspective to one’s existence, or if it

activates a renewed sense of wonder, or solves long-standing problems

or questions by re-casting their context, the process will have

been worthwhile.

This does not mean that everyone should rush out and find a past

life facilitator. There are many other ways of accessing the material

— dreams, active imagination, creative work, journaling, dialoguing

aloud with oneself —- and, the most common and miraculous way

of all: falling in love. As Tagore writes on the persistence of

love from past lives:

“I think I shall stop startled if ever we meet after our next birth, walking in the light of a far-away world. I shall know those dark eyes then as morning

stars, and yet feel that they have belonged to some unremembered

evening sky of a former life. I shall know that the magic of your

face is not all its own, but has stolen the passionate light that

was in my eyes at some immemorial meeting, and then gathered from

my love a mystery that has now forgotten its origin. Love then

can be a guide to past lives. And dreams, fantasies, musings,

and strong likes and dislikes for foods, clothes, furniture, art,

colors. All these ingredients offer hints of where we have been

before, with whom, and in what context. It may be that we do not

live many earlier lives, but rather that we live only one, always

the same, but lived in different costumes and played out on many

different stages, with many of the same supporting actors, over

and over and again over, as we garner new insights and greater

compassion each time.”

Much more could be said, for the subject is complex and fascinating,

but since I only wish to touch on a few perspectives concerning

past lives, this must suffice. For those who wish to pursue the

matter further, I offer a selected bibliography below.

FOOTNOTES::

1 Head & Cranston [see bibliography]:412.

2 Head & Cranston: 258.

3 Eliade, Mircea. Myth & Reality: 121.

4 Ibid.: 122.

5 Ibid.:116.

6 Ibid.:90.

7 Downing, Christine. Gods in Our Midst. New York: Crossroad, 1993:48.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Note: there are a huge number of books on these topics and I have certainly not read them all. Of those I have (mostly from the days of my initial involvement in the field), these are among my favorites. Many are classics and still in print. [Added 8 February 2004]: This is a fine review of a scholarly book that looks quite intriguing — Gananath Obeyesekere’s Imagining Karma: Ethical Transformation in Amerindian, Buddhist, and Greek Rebirth. (Comparative Studies in Religion and Society Series, vol. 14. Berkeley and London: University of California

Press, 2002.) Here is the review: http://www.h-net.msu.edu/reviews/showrev.cgi?path=4601070867937

Cerminara, Gina. Many Mansions. New American Library/Signet, 1950.

Cranston, Sylvia, and Carey Williams. Reincarnation: A New Horizon in Science, Religion, & Society. Crown, 1984.

Head, Joseph, and S. L. Cranston, eds. Reincarnation in World Thought. Julian Press, 1967.

Lucas, Winafred Blake, Ph.D. Regression Therapy: A Handbook for Professionals (in 2 volumes). Deep Forest Press, 1993.

MacGregor, Geddes, Ph.D. Reincarnation in Christianity. Quest Books, 1978.

Moody, Raymond A., Jr., M.D. Life After Life. Bantam, 1976.

Moore, Marcia. Hypersentience. Crown, 1976. [Note: Marcia Moore was my guide and teacher in the very beginning of my past life experiences.]

Stearn, Jess. The Search for a Soul: Taylor Caldwell’s Psychic Lives. Fawcett Crest, 1974.

For Children (but I also love this one too):

Gerstein, Mordicai. The Mountains of Tibet. HarperCollins / Harper Trophy, 1989.

Source for both articles:

Kathleen Jenks, Ph.D.

The author is a former professor of mythology at California’s Pacifica Graduate Institute who has now returned to private practice as a past life facilitator in southwest Michigan.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

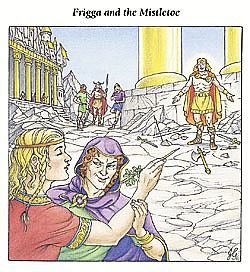

Holda’s

Holda’s

On summer solstice morning, Balts anxiously awaited the sunrise,

On summer solstice morning, Balts anxiously awaited the sunrise,

A past life is simply a life you lived before your current life. You lived it in a different body, often a different gender, a different race, with different parents and friends, different dreams and beliefs, different priorities, different skills, different loves, hates, and fears. Were you to meet that earlier “you,”

A past life is simply a life you lived before your current life. You lived it in a different body, often a different gender, a different race, with different parents and friends, different dreams and beliefs, different priorities, different skills, different loves, hates, and fears. Were you to meet that earlier “you,” It is said that we need all these varied experiences and roles to be whole. Another way to approach this is to say that we only live one life, but in many different bodies and circumstances. We might say that we are like a kaleidoscope filled with thousands

It is said that we need all these varied experiences and roles to be whole. Another way to approach this is to say that we only live one life, but in many different bodies and circumstances. We might say that we are like a kaleidoscope filled with thousands We rarely know that archetypes exist unless something happens to activate one. Even then, most people do not understand what has been activated or what it means. An “archetype” can perhaps best be understood as an energy-field within the psyche.

We rarely know that archetypes exist unless something happens to activate one. Even then, most people do not understand what has been activated or what it means. An “archetype” can perhaps best be understood as an energy-field within the psyche.

The twenty-two cards of the Tarot’s Greater Arcana are another source

The twenty-two cards of the Tarot’s Greater Arcana are another source

Let’s use the example of a riptide for the Hermit archetype. This is

Let’s use the example of a riptide for the Hermit archetype. This is

If we have had past lives, we have also obviously had past deaths.This fact is a major reason why people are interested in exploring their past lives — it places the inevitability of death in a much larger context and makes it far less fearsome. It also gives

If we have had past lives, we have also obviously had past deaths.This fact is a major reason why people are interested in exploring their past lives — it places the inevitability of death in a much larger context and makes it far less fearsome. It also gives

what

what No matter what we call it, the memories are there and most people

No matter what we call it, the memories are there and most people

How does all this relate to Druidic history? Well, history is speculation and PR. The accounts of what happened that far in the past were written by people who were not part of the culture. Tacitus, for all his historical records, was pretty much a “tabloid” writer. I’ve read several of his accounts of different cultures

How does all this relate to Druidic history? Well, history is speculation and PR. The accounts of what happened that far in the past were written by people who were not part of the culture. Tacitus, for all his historical records, was pretty much a “tabloid” writer. I’ve read several of his accounts of different cultures

jails, many have been tortured, and several of her friends and family have been lynched by enraged mobs.

jails, many have been tortured, and several of her friends and family have been lynched by enraged mobs.