“Ye shall take note of the decline of the Sun in the sky, which doth begin on the day of Midsummer. Ye shall light your fires and let them die in token of the great fire which doth roll down in the sky even as a

ball doth roll down a hill.”

– DC(R) The Book of the Law, 4:6

The Summer Solstice is a Minor High Day, usually occurring around June 20th or so. It is also known as: Alban Heflin, Alban Heruin, All-couples day, Feast of  Epona, Feast of St. John the Baptist, Feill-Sheathain, Gathering Day, Johannistag, Litha, Midsummer, Sonnwend, Thing-Tide, Vestalia, etc.

Epona, Feast of St. John the Baptist, Feill-Sheathain, Gathering Day, Johannistag, Litha, Midsummer, Sonnwend, Thing-Tide, Vestalia, etc.

“Solstice” is derived from two Latin words: “sol” meaning sun, and “sistere,” to cause to stand still. This is because, as the summer solstice approaches, the noonday sun rises higher and higher in the sky on each successive day. On the day of the solstice, it rises an imperceptible amount, compared to the day before. In this sense, it “stands still.”

Most societies in the Northern Hemisphere, ancient and modern, have  celebrated a festival on or close to Midsummer: Ancient Celts: Druids, the

celebrated a festival on or close to Midsummer: Ancient Celts: Druids, the

priestly/professional/diplomatic corps in Celtic countries, celebrated Alban Heruin (“Light of the Shore”). It was midway between he spring Equinox (Alban Eiler; “Light of the Earth”) and the fall Equinox (Alban Elfed; “Light of the Water”). “This midsummer festival celebrates the apex of Light, sometimes

symbolized in the crowning of the Oak King, God of the waxing year. At his crowning, the Oak King falls to his darker aspect, the Holly King, God of the waning year…” The days following Alban Heruin form the waning part of the year because the days become shorter.

The Oak King defeats the Holly King on the longest day of the year. The Holly King and the Oak King are part of Celtic mythology, and they represent two sides to the Green Man, or Horned God.

They battle twice a year, once at Yule and once at Midsummer (Litha) to see who would rule over the next half of the year. At Yule, the Oak King wins and at Litha, the Holly King is victorious. In other words, the Oak King rules over the lighter half of the year, and the Holly King over the darker half. The change from one to the other is a common theme for rituals at Yule, and also at Midsummer. Another version of the Holly King and Oak King symbolism, is that

who would rule over the next half of the year. At Yule, the Oak King wins and at Litha, the Holly King is victorious. In other words, the Oak King rules over the lighter half of the year, and the Holly King over the darker half. The change from one to the other is a common theme for rituals at Yule, and also at Midsummer. Another version of the Holly King and Oak King symbolism, is that

they do not directly switch places twice a year, but rather both live simultaneously. The Oak King is born at Yule, and his strength grows through the spring, peaks at Beltane and then he weakens and dies at Samhain. The

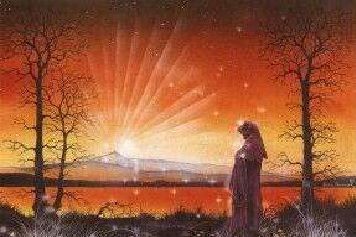

Holly King lives a reverse existence, and is born at Midsummer, waxes more powerful through the summer and fall, to his peak at Samhain. His influence then lessens until Beltane, when it is his turn to pass away. In this perspective, the two Kings enjoy a more intricate interplay of power and is perhaps a better illustration of their duality. At any given time, they both exist but have varying levels of influence throughout the year. Either way, each King represents different ideas. The time of the Oak King is for growth, development, healing, and new projects. The Holly King’s time is for rest, reflection, and learning. This Holiday shares mythical elements with both Beltane and Lughnasadh. Like both, it is a feast celebrating the glory of Summer and the peak of the Sun  God‘s power. But in many systems of belief, it is the day of the biggest battle of the year between the Dark Sun God and the Lugh Sun God (or between the evil one and the good one), Who are usually brothers or otherwise intimately related. Midsummer is a peak from which the Sun can only fall, for it is the day on which the hours of light slowly begin to shorten. In those areas where it is safe to do so,

God‘s power. But in many systems of belief, it is the day of the biggest battle of the year between the Dark Sun God and the Lugh Sun God (or between the evil one and the good one), Who are usually brothers or otherwise intimately related. Midsummer is a peak from which the Sun can only fall, for it is the day on which the hours of light slowly begin to shorten. In those areas where it is safe to do so,

Neopagans frequently will light cartwheels of kindling and roll them down from the tops of high hills, in order to symbolize the falling of the Sun God. Just as the Pagan midwinter celebration of Yule was adopted by Christians as Christmas (December 25th), so too the Pagan mid-summer celebration was adopted by them as the feast of John the Baptist (June 24th). Occurring 180 degrees apart on the wheel of the year, the midwinter celebration commemorates the birth of Jesus, while the mid-summer celebration

commemorates the birth of John, the prophet who was born six months before Jesus in order to announce his arrival.

Although modern Druids often refer to the holiday by the rather generic name of Midsummer’s Eve, it is more probable that our Pagan ancestors of a few hundred years ago actually used the Christian name for the holiday, St. John’s Eve. This is evident from the wealth of folklore that surrounds the Summer Solstice (i.e. that it is a night especially sacred to the faerie folk) but which is inevitably ascribed to ‘St. John’s Eve,’ with no mention of the Sun’s position. It could also be argued that a Grove’s claim to antiquity might be judged by what name it gives the holidays. (Incidentally, the name ‘Litha’ for the holiday is a modern usage, possibly based on a Saxon word that means the opposite of Yule. Still, there is little historical justification for its use in this context.)

But weren’t our Pagan ancestors offended by the use of the name of a Christian saint for a pre-Christian holiday? Well, to begin with, their theological sensibilities may not have been as finely honed as our own. But secondly and more importantly, St. John himself was often seen as a rather Pagan figure. He was, after all, called ‘the Oak King.’ His connection to the wilderness (from whence ‘the voice cried out’) was often emphasized by the rustic nature of his shrines. Many statues show him as a horned figure (as is also the case with Moses). Christian iconographers mumble embarrassed explanations about ‘horns of light,’ while modern Pagans giggle and happily refer to such statues as ‘Pan the Baptist.’ And to clinch matters, many depictions of John actually show him with the lower torso of a satyr, cloven hooves and all! Obviously, this kind of John the Baptist is more properly a Jack in the Green! Also obvious is that behind the medieval conception of St. John lies a distant, shadowy Pagan deity, perhaps the archetypal Wild Man of the Wood, whose face stares down  at us through the foliate masks that adorn so much church architecture. Thus medieval Pagans may have had fewer problems adapting than we might suppose. In England, it was the ancient custom on St. John’s Eve to light large bonfires after sundown, which served the double purpose of providing light to the revelers and warding off evil spirits. This was known as ‘setting the watch.’ People often jumped through the fires for good luck. In addition to these fires, the streets were lined with lanterns, and people carried cressets (pivoted lanterns atop poles) as they gwialenered from one bonfire to another. These gwialenering, garland bedecked bands were called a ‘marching watch.’ Often they were attended by Morris dancers, and traditional players dressed as a unicorn, a dragon, and six hobby-horse riders.

at us through the foliate masks that adorn so much church architecture. Thus medieval Pagans may have had fewer problems adapting than we might suppose. In England, it was the ancient custom on St. John’s Eve to light large bonfires after sundown, which served the double purpose of providing light to the revelers and warding off evil spirits. This was known as ‘setting the watch.’ People often jumped through the fires for good luck. In addition to these fires, the streets were lined with lanterns, and people carried cressets (pivoted lanterns atop poles) as they gwialenered from one bonfire to another. These gwialenering, garland bedecked bands were called a ‘marching watch.’ Often they were attended by Morris dancers, and traditional players dressed as a unicorn, a dragon, and six hobby-horse riders.

Just as May Day was a time to renew the boundary on one’s own property, so Midsummer’s Eve was a time to ward the boundary of the city. Customs surrounding St. John’s Eve are many and varied. At the very least, most young folk plan to stay up throughout the whole of this shortest night. Certain courageous souls might spend the night keeping watch in the center of a circle

of standing stones. To do so would certainly result in either death, madness, or

(hopefully) the power of inspiration to become a great poet or bard. (This is, by the way, identical to certain incidents in the first branch of the ‘Mabinogion.’) This was also the night when the serpents of the island would roll themselves into a hissing, writhing ball in order to engender the ‘glain,’ also called the ‘serpent’s egg,’ ‘snake stone,’ or ‘Druid’s egg.’ Anyone in possession of this hard glass bubble would wield incredible magical powers. Even Merlin himself (accompanied by his black dog) went in search of it, according to one ancient Welsh story. Snakes were not the only creatures active on Midsummer’s Eve. According to British faery lore, this night was second only to Halloween for its

According to British faery lore, this night was second only to Halloween for its

importance to the wee folk, who especially enjoyed a riddling on such a fine summer’s night. In order to see them, you had only to gather fern seed at the stroke of midnight and rub it onto your eyelids. But be sure to carry a little bit of rue in your pocket, or you might well be ‘pixie-led.’ Or, failing the rue, you might simply turn your jacket inside-out, which should keep you from harm’s way. But if even this fails, you must seek out one of the ‘ley lines,’ the old straight tracks, and stay upon it to your destination. This will keep you safe from any malevolent power, as will crossing a stream of ‘living’ (running) water. Other customs included decking the house (especially over the front door) with birch, fennel, St. John’s wort, orpin, and white lilies.

Five plants were thought to have special magical properties on this night: rue, roses, St. John’s wort, vervain and trefoil. Indeed, Midsummer’s Eve in Spain is called the ‘Night of the Verbena (Vervain).’ St. John’s wort was especially honored by young maidens who picked it in the hopes of divining a future lover. There are also many mythical associations with the Summer Solstice, not the least of which concerns the seasonal life of the God of the sun. In Irish mythology, Midsummer is the occasion of the first battle between the Fir Bolgs and the Tuatha De Danaan.

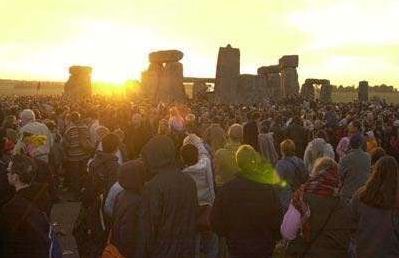

Altogether, Midsummer is a favorite holiday for many Druids in that it is so hospitable to outdoor celebrations – and a favorite modern custom is to travel to Stonehenge and gather to wait for the Midsummer sunrise. The warm summer night seems to invite it. And if the celebrants are not in fact sky clad, then you may be fairly certain that the long ritual robes of winter have yielded place to short, tunic-style apparel. As with the longer gowns, tradition dictates that one should wear nothing underneath — the next best thing to sky clad, to be sure. (Incidentally, now you know the REAL answer to the old Scottish joke, ‘What is worn underneath the kilt?’)

The two chief icons of the holiday are the spear (symbol of the Sun-God in his glory) and the summer crochan (symbol of the Goddess in her bounty). The precise meaning of these two symbols will be explored in the essay on the death of Llew. But it is interesting to note here that modern Druids often use these same symbols in the Midsummer rituals. And one occasionally hears the alternative consecration formula, ‘As the spear is to the male, so the crochan is to the female…’ With these mythic associations, it is no wonder that Midsummer is such a joyous occasion!